Useful insights in designing an Illustrated space

Have you ever wondered how illustrators create their pictures? It seems easy, until you actually try to do it.

Many pictures for The Little Cleveland take place in the Wellesley Hills Branch Library. Because I live so close, I was able to go there often and draw the interior from several vantage points. One problem dealt with - sort of. A bigger issue was how do you put people in the space, so that they don't look like they are floating, unrelated, too small or too big? And, where is the best point of view? Should the bar always be the backdrop? Probably not.

Some of the tools & methods I use that are discussed in this blog.

How do you populate the space with people? Pubs are social places, so there should probably be several patrons. What are they doing? How can people, who are not the center of interest, enhance the action of the main characters? And from a design perspective, how do you draw and place these extra people so that they don't distract from the main action?

You could build a physical model and draw the objects. I did not do that. Instead, I used advice I got out of a book called Composing Pictures by Donald W. Graham (1970 Litton Educational Publishing, Inc.) Graham had a long career teaching artists and illustrators at the Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of Arts), the Disney Studio training school, and others.

The first time I tackled this detailed, somewhat difficult book was 2011, after I had rotator cuff surgery on my right shoulder. Being a righty, I couldn't draw, so I spent many summer hours on my front porch reading his lessons and trying to understand them. It's the kind of book you keep going back to if you are an artist who really likes to get into the weeds of design.

The most important lesson I learned that summer was how to place people and objects in a space, and how to draw them from any angle. The technique Graham explained to get many viewpoints is called the whirling plan. Rembrandt used it; I haven't been able to find it on google.

Briefly, you start by sketching a scene, maybe two people sitting at a table. You then draw a bird's eye view of the scene. By rotating this bird's eye view, and dropping the people and objects straight down to a normal view, you can visualize many different viewpoints. This explanation does not really tell you how to use the whirling plan. If you are interested in finding out how to use this technique, leave me a comment, or get Graham's book.

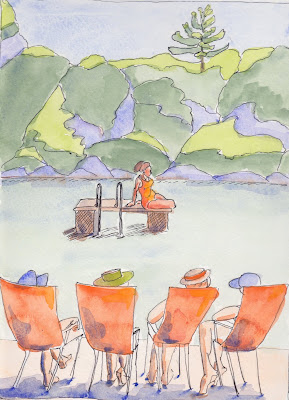

The neat thing about this method is that as your view changes, other people who are in the room you are drawing may come into view. Their presence may inform or amplify the action of the main characters.

In this image of my Uncle Jimmy flipping a coin to see which of his nieces, my two older sisters Sue and Mary Beth, would get the last pierogi, I show Rusty, the bartender, looking on.

(I cringe when I look at this piece - look at how big Uncle Jimmy's right hand is! Ouch!)

If I hadn't tried different vantage points, it never would have occurred to me to include Rusty and his quizzical expression.

Another technique I learned is to draw from the back of the picture forward. Think of it as placing actors on a stage - you place those in the back first, then those in the middle, then those in the foreground. Renoir used this technique. Despite the fact that his work goes in and out of fashion, he was a master at placing many people in a painting.

I drew everything in blue pencil first, because it does not show up when scanned - although it appeared when I took a picture with my phone.

In this illustration, my neighbor confronts my beleaguered mother about the damage that rabbits caused in his vegetable garden. My Uncle Norm had found two jackrabbits on a golf course and brought them, to his nieces and nephews delight, to our house. He erected a makeshift pen out of picnic benches. Rabbits being rabbits, they immediately jumped out of their pen and hightailed it to Mr. Prusha's vegetable garden, where they had quite a feast.

I placed the action in the garage, as my mother unloads groceries from one of her never-ending food shopping trips. Again, I used the background to inform the main action. A tricycle and bicycle are stationed underneath treacherous gardening tools. They illustrate, for me, some of the perils of childhood.

Also, look closely at the picture. You can see the underdrawing of the background, with the foreground objects drawn right over it.

In summary, I used a few really useful techniques when I wrote and illustrated The Little Cleveland. I continue to use them. They are:

- Look at the action from different vantage points. You can often amplify the action and emotion of the scene you are illustrating.

- Start drawing objects in the background first. Then, stack the middle ground, and finally the foreground objects on top of these. Either draw very lightly with a soft pencil (easiest to erase) or a blue pencil (some people don't like them because they are waxy.)

Next time - growing as an illustrator, and looking back at earlier work.